The Sinking of the Lisbon Maru

I came to hear about the Lisbon Maru from my dad, Albert Ient, when I was a child. He told me of the terrible (and fatal for many) journey a number of his fellow Prisoners of War (POWs) had on the Lisbon Maru when they were transported to Japan, following the fall of Hong Kong, to be interned in labour camps for the rest of World War Two (WWII).

I came to hear about the Lisbon Maru from my dad, Albert Ient, when I was a child. He told me of the terrible (and fatal for many) journey a number of his fellow Prisoners of War (POWs) had on the Lisbon Maru when they were transported to Japan, following the fall of Hong Kong, to be interned in labour camps for the rest of World War Two (WWII).

My dad was luckily in the lottery of allocation not to have been drafted onto this doomed ship, but no story of the events following the Battle for Hong Kong would be complete without reference to this tragic and harrowing event. My contribution to the records of the events relating to the sinking and what happened afterwards is in two parts: the account below and the account of one of the survivors who I interviewed in 2006. You can read about his story on this website, just go to: Maynard Skinner. Maynard was a fellow soldier of my dad’s in Hong Kong and, like dad, became a POW.

Please follow the links below to read about this story of tragedy and survival:

Research for this Document

Many Lives Lost

Leaving Shamshuipo

Confined to the Hold of the Ship

Food

Japanese Troops

The Torpedo Attack

Japanese Reports

5th and 6th Torpedo Attacks

In the Hold

Japanese Troops Evacuate the Ship

Hatches Closed Completely

Ship Sinking – Prisoners In Hold

The Break Out

Japanese Soldiers Fire on the PoWs in the Water

The Sinking Ship – POW Try to Swim

In the Sea

Survivors Picked Up

Railway Wharf in the Whangpoo River

Shanghai to Japan

The Casualties

Further Reading

Research for this Document

Survivors, like Maynard Skinner, remember with clarity their own part in this affair, but few know all the facts. To help get a clearer picture I have taken the following extracts from the BBC website WW2 People’s War. They tell the story of the Lisbon Maru based on accounts from Martin Weedon in his book, Guest of an Emperor; the newspaper accounts of the war crimes trials of the Japanese responsible; extracts from the log of USS Grouper, which torpedoed the Lisbon Maru; newspaper accounts in the Japan Times Weekly dated 20 October 1942; The Knights of Bushido, by Lord Russell of Liverpool; personal accounts written at the time; and personal reminiscences.

Many Lives Lost

In the annals of modern warfare, the sinking of the Lisbon Maru, as a result of which over 800 out of 1,800 men lost their lives, does not perhaps rate very high as a horror story. There have been many incidents in which many more people have been killed, in a more brutal fashion, but it stands out as an example of unnecessary killing, of callous disregard for human lives which could have been saved.

Leaving Shamshuipo

1,816 men from Shamshuipo Camp were divided into groups of 50, each group being in the charge of a subaltern, while the whole party was commanded by Lt. Col. H.W.M. (Monkey) Stewart, O.B.E., M.C., the Commanding Officer of the Middlesex Regiment (The Diehards), assisted by a small number of officers.

After an exhaustive but (as it turned out) ineffective medical examination, the prisoners were loaded on 27 September into lighters from the pier at the corner of Shamshuipo Camp and taken out to a freighter of some 7,000 tons, the Lisbon Maru, under the command of Captain Kyoda Shigeru.

Confined to the Hold of the Ship

The men were confined in three holds. In No.1 hold, nearest the bows, were the Royal Navy under the command of Lieut. J.T. Pollock. In No.2 hold, just in front of the bridge, were the Royal Scots (2nd Btn.), the Middlesex Regiment (1st Btn.), and some smaller units, all under Lt. Col. Stewart. In No.3 hold, just behind the bridge, were the Royal Artillery under Major Pitt. Conditions were very crowded indeed, with all the men lying shoulder to shoulder on the floor of the hold or on platforms erected at various heights. The officers on a small ‘tween’ deck halfway up the hold were similarly crowded.

Food

Food was quite good by prisoner of war standards: rice and tea in the morning, and rice, tea and a quarter tin of bully beef with a spoonful of vegetables in the evening. There was sufficient water for drinking, but none for washing. Some cigarettes were issued – a great luxury. The latrines consisted of wooden hutches hanging over the side of the ship and were too few for the numbers on board. About half the men were provided with kapok life belts. At the subsequent war crimes trial, Interpreter Niimori claimed that every man had a life belt, which he checked at every roll call.

Japanese Troops

Also on board were 778 Japanese troops and a guard of 25 under the command of Lieut. Hideo Wada. The ship sailed on 27 September. The first four days were uneventful. The weather was good and the prisoners were allowed on deck in parties for fresh air and exercise. There were four lifeboats and six life rafts, and according to the captain it was decided that the four lifeboats and four of the rafts should be set aside for the Japanese if required, leaving two life rafts for the 1,816 prisoners.

The Torpedo Attack

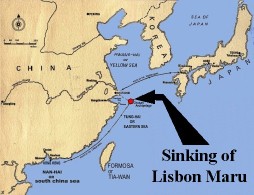

On the night of 30 September 1942, the USS Grouper (left), belonging to Division 81 of the United States Pacific Fleet Submarine Force, was engaged in its second war patrol in an area south of Shanghai. It was a bright moonlight night, and at about 4 am Grouper sighted about nine sampans and a 7,000 ton freighter, the Lisbon Maru. Her commanding officer decided that the night was too bright for a surface attack, so he paced the target in order to determine her course and speed, and then took up a position ahead of the ship to await daylight on 1 October. While he was doing so, he passed within 4,000 yards of two fishing boats equipped with fishing lights and side-lights.

On the night of 30 September 1942, the USS Grouper (left), belonging to Division 81 of the United States Pacific Fleet Submarine Force, was engaged in its second war patrol in an area south of Shanghai. It was a bright moonlight night, and at about 4 am Grouper sighted about nine sampans and a 7,000 ton freighter, the Lisbon Maru. Her commanding officer decided that the night was too bright for a surface attack, so he paced the target in order to determine her course and speed, and then took up a position ahead of the ship to await daylight on 1 October. While he was doing so, he passed within 4,000 yards of two fishing boats equipped with fishing lights and side-lights. At daylight, the Lisbon Maru changed course about 50 degrees leaving the submarine in a poor position from which to attack. She dived and began her approach at 7:04 am. She fired three torpedoes at the closest range attainable (3,200 yards) but scored no hits. The ship remained on course; the commander fired a fourth torpedo and in two minutes ten seconds heard a loud explosion. He raised the telescope and found that the ship had changed course about 50 degrees to the right and had then stopped. There was no visible sign of damage. The Grouper then headed for a position abeam to starboard for a straight bow shot. The commander then continues his report: 'Target meanwhile hoisted flag resembling “Baker” and was firing at us with what sounded like a small calibre gun. Sharp explosions all around us.'

At daylight, the Lisbon Maru changed course about 50 degrees leaving the submarine in a poor position from which to attack. She dived and began her approach at 7:04 am. She fired three torpedoes at the closest range attainable (3,200 yards) but scored no hits. The ship remained on course; the commander fired a fourth torpedo and in two minutes ten seconds heard a loud explosion. He raised the telescope and found that the ship had changed course about 50 degrees to the right and had then stopped. There was no visible sign of damage. The Grouper then headed for a position abeam to starboard for a straight bow shot. The commander then continues his report: 'Target meanwhile hoisted flag resembling “Baker” and was firing at us with what sounded like a small calibre gun. Sharp explosions all around us.'

On board the ship, the prisoners heard and felt the explosion, after which the engines stopped and the lights went out; but they did not know whether the ship had been torpedoed or whether there had been an internal explosion in the engine room. There was wild activity and shouting among the Japanese; some prisoners who were up on deck were hustled and pushed into the holds, and the ship’s gun began firing. About ten sick men, who had been allowed to remain permanently on deck, were also sent down into the packed holds, with an order that they should be 'isolated'. In the holds, the prisoners sat gloomily, wondering what was happening and whether they were going to get any breakfast.

Japanese Reports

The account in the Japan Times Weekly of 20 October 1942 was different:

'"We must rescue the British prisoners of war" was the foremost thought which leaped into our minds when the ship met the disaster,” said Lieut. Hideo Wada. “It was just the hour for the roll call of prisoners; somewhat taken aback, they were about to stampede. "Don’t worry," we told them. "Japanese planes and warships will come to your rescue." The commotion died down. It was encouraging to note that they had come to have such trust in the Imperial Forces during a brief war prisoners’ camp life.'

5th & 6th Torpedo Attacks

By 8:45 am, USS Grouper had reached a firing position for a 0 degree gyro, 80 degree track, range 1,000 yards. She fired the 5th torpedo with a 6 foot depth setting, but missed. The ship had now developed a slight list to starboard. The Commander did not wish to use another bow torpedo so he worked around to a position 1,000 yards on the port side and at 9:38 am fired a 6th torpedo from the stern tube, 180 degrees gyro, 80 degrees track, with a depth setting of 0 feet. He did not wait to see the results but immediately went to a 100 feet dive and heard a loud explosion 40 seconds later, 'definitely torpedoish'.

It is doubtful whether this 6th torpedo hit. The prisoners did not observe it, but it could have passed unnoticed among the depth charges exploding around the ship. The Japanese claim to have destroyed this torpedo. 'It was just about 10:30 am that I happened to discover the 6th torpedo rushing towards the ship,' said one of the gunners. 'Corporal Moji gave us the order to fire at the torpedo …. Surprised beyond words, but faithful to the order, we charged our cannon with a shell, aimed at the torpedo, and fired. We looked ahead of us and discovered that we had scored a direct hit.'

The submarine then came up to periscope depth. The ship had disappeared and the commander assumed, incorrectly, that she had sunk.

In the Hold

On board the Lisbon Maru, the Japanese had calmed down but had become uncooperative. Requests for food and water were refused. There was no latrine accommodation in the holds and many of the men were suffering from dysentery or diarrhoea. Requests for permission to attend the latrines on deck or for receptacles to be passed down were ignored.

The submarine stayed in the vicinity throughout the day, occasionally hearing depth charges, as did the prisoners on the ship. Dusk settled, the sky was overcast and visibility through the periscope was poor. At 7:05 pm, the commander sighted lights astern and he decided to surface 'and remove ourselves while the going was good'.

For the prisoners, it was a long, uncomfortable and increasingly anxious day. It was by now clear that the ship had been disabled and was listing, but the prisoners had no means of knowing the extent of the damage or what measures were being taken for their relief.

Over the course of the day, the Japanese partially closed the hatches, leaving a canvas wind funnel through which some air could reach the men in the hold.

Japanese Troops Evacuate the Ship

According to the evidence of Captain Kyoda Shigeru, master of the Lisbon Maru, at his trial in Hong Kong in October 1946, the Japanese destroyer 'Kure' arrived at the scene during the afternoon of 1 October and an order was received about 5 pm to transfer all the 778 Japanese troops to the destroyer. While this transfer was taking place, with the aid of two lifeboats, the 'Toyokuni Maru' arrived under Captain Yano, and a conference was held on board the Lisbon Maru at which it was decided that the remaining Japanese troops should be transferred to the Toyokuni Maru and not to the Kure. The 77 members of the crew and the 25 guards under Lieut. Wada were to remain on the Lisbon Maru and arrangements were made for her to be towed to shallow water.

Hatches Closed Completely

After the Japanese troops had been removed to safety, Capt Kyoda Shigeru and Lieut. Wada discussed what should be done about the prisoners. According to the captain, Lieut. Wada said that it was impossible for 25 guards to guard 1,816 prisoners and that the best solution would be to close the hatches. The captain said that he objected to the closing of the hatches on the grounds that ventilation would become very bad and also that if there were another attack and the ship sank with the hatches closed, there would be a needless waste of lives.

Wada appeared to accept this, but, according to the captain, at about 8 pm one of the guards came and adopted a very truculent attitude. He told the captain that the guards did not wish to be killed by the POWs and asked why the hatches should not be closed. The captain asked the guard if he was a soldier, and he then left. At about 9 pm, Wada came to the bridge and ordered the captain to have the hatches closed. Wada said that he was responsible for guarding the POWs and that the master of the ship had no authority to interfere. The attitude of Wada was very threatening, so the captain ordered the first officer to close the hatches.

On the instruction of Lieut. Wada, who, according to the official account in Japan Times Weekly, 'directed the rescue atop the mast of the sinking Lisbon Maru', the hatches were then closed, canvas tarpaulins were stretched over them and roped down, leaving the prisoners in complete darkness. As the night wore on, the air became very foul indeed, and men began to wonder how long they could survive. No food had been received for over 24 hours and most men had finished the small ration of water in their water bottles. It was also over 24 hours since the prisoners had been to the latrines, and in the packed holds, with everyone shoulder to shoulder, no facilities could be improvised. But despite these discomforts the men remained calm, and were reassured by Col. Stewart’s insistence that even the Japanese would not abandon a ship and kill all the POWs. Indeed morale remained remarkably high. CQMS Henderson, of the Royal Scots in particular, his beard jutting out aggressively, encouraged non-swimmers like himself by insisting that now was the time to learn. Repeated attempts by Lieut. Potter of the St John Ambulance Association, who spoke Japanese, to communicate with the guards on deck brought no response.

In the course of the long night, Col. Stewart decided to prepare for a break out. He accordingly approached Lieut. H.M. Howell, who was something of an expert in these matters, having been in two previous shipwrecks, and ordered him to try and make a hole in the hatch covers. One of the resourceful British troops produced a long butcher’s knife which had escaped the eyes of the Japanese searchers. Armed with this, Lieut. Howell mounted an iron ladder in pitch blackness and tried to make an opening. Having to hold on to the ladder with one hand and suffering from a lack of oxygen, he was unable to effect any purchase, and was obliged to abandon the attempt.

Ship Sinking – Prisoners Left Sealed in the Hold

By dawn on 2 October, it was apparent to Capt. Kyoda Shigeru, according to his evidence at his trial, that the ship was in imminent danger of sinking, and he sent a flag message to the Toyokuni Maru at 8:10 am asking permission for everyone to abandon ship. At 8:45 am, he was informed that a ship would be sent alongside to take off the Japanese guards and the crew, but NOT the prisoners. 'All the Japanese, of course, were prepared to share a common fate with the British Prisoners of War,' said the official Japanese account. 'That was why we all put on our life-buoys at the same time.' It seems probable, in fact, that nearly ALL the Japanese had been removed from the ship at this time, leaving only a small rearguard of about five guards to keep the prisoners from escaping.

The Break Out

By about 9 am, 24 hours after the torpedoing, the air in the holds was dangerously foul and it was evident that the men could not survive much longer. Then the ship gave a heavy lurch and it was apparent that she could not last much longer. Lt. Col. Stewart ordered Lieut. Howell to try again to force the hatch covers. This time he found the rickety wooden staircase which led to the hatch cover. He mounted the stairs, forced his knife between the timbers, cut the rope, sliced the tarpaulin and then with great effort forced up one of the baulks of timber.

He then climbed through the aperture, followed by Lieut. Potter and a few other men. After reporting to Lt. Col. Stewart that he could see an island, Howell noticed some British gunners from No. 3 hold struggling to get out through portholes on to the well deck. He unscrewed a bulkhead door to release them and then made a second opening in the hatch at the point where the iron rung ladder led up from the hold.

Japanese Soldier Open Fire on the POWs in the Water

The Japanese (it is believed that only about five of them were left by this time) had taken no action up to this point, but they now opened fire from the bridge. Howell ducked and the shots went through the hole that Howell had made, killing one man in the hold and slightly injuring Lieut. G.C. Hamilton (author of this account). The Japanese then fired again at the escape party and wounded Lieut. Potter. Lieut. Howell assisted him back into the hold, where he died.

As soon as Lt. Howell returned to the hold, he was asked by Lt. Col. Stewart about the state of the ship. There was a long pause in the silence of the hold before Howell replied that the position was desperate and that the ship would sink at any moment. The ship then gave a further lurch; possessions began to slide across the hatch and water poured in through the first opening in the hatch which Howell had made. Lt. Col. Stewart then gave the order for all to leave the hold. This was soon after 9 am. Led by Howell, a number of men rushed up the staircase onto the deck and plunged over the side of the ship into the water, where they started to swim towards the islands. They were fired at from the bridge and some were hit.

The Sinking Ship – POWs Try to Swim to Island

For the first time since the torpedo struck the ship, there was panic in the hold, as men raced up the wooden stairway and climbed the iron ladders, desperately trying to push aside the heavy baulks of timber. Some men climbed over each other’s shoulders, some fell to the bottom of the hold, and there was great noise and shouting. But this lasted for only a short time and order was quickly restored, with the men forming long queues at the stairways and ladders.

Water continued to pour in through the openings in the hatch and there seemed little hope of getting out before the ship sank. In the dim light which filtered into the hold, Capt. Cuthbertson, Adjutant of the Royal Scots, carefully put on his Tam O’Shanter, and in reply to a question on whether caps were to be worn on this parade answered that he preferred to meet his God properly dressed. Had the ship sunk at this stage, few would have escaped, but by good fortune the stern had come to rest on a sandbank leaving the forepart of the ship as far as the bridge sticking out of the water, with successive waves pouring into the hold. She remained in this position for about an hour, which gave sufficient time for all live men to climb or be assisted out of the three holds.

On arrival on deck, some men immediately plunged into the water, while others remained on deck, wondering at their survival and seeking some place where they could at last respond to a long outstanding call of nature. Some men threw ropes down into the hold to increase the number of exits, and Lt. Col. Stewart, despite a bad leg, climbed one of the ropes and was helped onto the deck, immaculate as usual, complete with cap and swagger cane. Captain Cuthbertson, the last to leave the No. 2 hold, first descended to the bottom to ensure that no live person remained there. Lt. J.T. Pollock, RN, who had been entrusted by the officers in Hong Kong with some funds for the use of the men in Japan, went back into No.1 hold and succeeded in rescuing the money. By this time, the firing had stopped, for there were no longer any Japanese on board. Where or how they had gone remains a mystery, but it seems probable that the gunners, released by Howell into the well deck, had managed to make their way to the bridge, and had effectively silenced them. It is certainly NOT possible to believe Captain Kyoda’s claim at his trial that he remained on board and assisted the prisoners to launch rafts, or, according to the official report: 'remained on the bridge until the last of the prisoners was transferred to the lifeboats.'

It was pleasant on deck in the sunshine of a bright October day. Some men sat quietly down in the bows of the ship and discussed what they should do next. Some produced rare cigarettes. About five miles to the west were some islands; this looked like a long swim for men in poor condition. Moreover, a large proportion of the men had no life belts. Major Walker, second in command of the Royal Scots, gave his life belt to a non-swimmer and was not seen again.

Near at hand, to the west, between the ship and the islands, were a number of Japanese auxiliary vessels and tugs, some of them surrounded by men in the water vainly asking to be picked up and being pushed back into the water, and the firing of shots could be heard. To the east was the open sea. This to some looked inviting, since death by drowning in the open air seemed almost attractive by comparison with the rigours of the hold or the indignity of a futile attempt to be rescued by the inhospitable Japanese ships.

In the Sea

The matter was again decided by accident because there was a strong tide flowing westward towards the Japanese ships and the islands. In fact, it was the incipient tidal wave, famous in Hangehow Bay at that time of year. As men plunged into the sea, hanging onto boxes, baulks of timber or even dismantled latrines, they were carried inexorably in that direction. While they were in the water, there was the sound of another explosion; looking back, they saw the bows of the ship sinking beneath the waves. The time was about 10:30 am. At some stage further, orders must have been issued, for the Japanese boats started to pick up those prisoners who had not yet drifted past them towards the islands. The reason for this policy is not known, but it seems possible that the Japanese, observing that some men were reaching the islands and would tell their story, decided that they had better rescue those who still remained.

Survivors Picked Up

The islands, which had been seen from the ship, turned out to be the Sing Pang Islands in the Chusan Archipelago off the coast of Chekiang Province. The coast was rocky and the powerful tide dashed against the seaward faces of the cliffs. Howell was one of the first to reach the largest of the islands and was picked up by sampan. Speaking Shanghai dialect, he was able to explain to the villagers that the swimmers bobbing about in the water were British prisoners of war and not Japanese, whose fate the Chinese villagers had been contemplating with equanimity. As a result, the Chinese set off in junks and sampans in order to assist the survivors. They picked up a considerable number of exhausted swimmers, while other villagers assisted those who had swum or had drifted to the islands and helped them to land on the rocky shore. Many, however, were unable to obtain a footing and were swept past the islands and eventually drowned. Some 200 survivors were assembled on the islands, where the villagers fed and clothed them from their own scanty supplies and treated them with great kindness, until the Japanese landed a force from destroyers on the following day and collected all but three of the prisoners. These three, Mr A.J.W. Evans, Manager of the British Cigarette Co., Mr W.C. Johnstone and Mr Wallace, were hidden by the village representative, Mr Woo Tung Ling, who later arranged their escape to Chungking.

Those who were picked up in the water by Japanese vessels were collected together on the deck of a large gunboat which for three days and nights steamed around collecting survivors from the islands and, presumably, waiting for orders. The prisoners, who had previously suffered the intense heat of Lisbon Maru’s holds, now had to endure the cold and exposure of the deck, which was partially protected by a tarpaulin. Rain fell, the tarpaulin leaked, and the best clothed of the prisoners possessed only a shirt and a pair of shorts. Others were clad only in underpants, and a few were naked. Food was very scanty. When rations were first issued on the night of 2 October, no one had touched any food for two days. For the next three days, food consisted of a twice-daily ration of two biscuits and a cigarette tin of warm soya bean milk. Then, at last, when some men had died from exposure and exhaustion, the gunboat sailed for the Railway Wharf in the Whangpoo River, halfway between Woosung and Shanghai, where the prisoners were landed on the docks on 5 October. There were many pleasant reunions as friends met each other again, but there were also many absent faces.

Railway Wharf in the Whangpoo River - The Roll Call

Then began the group roll call taken by the subaltern in charge or by the senior NCO, assisted by Interpreter Niimori who beat the men into line with a stick. There were many who did not answer their names. Out of 50 prisoners of war in Group 20, 26 men, including C.Q.M.S. Henderson, were no longer there. Less than half of Lt. Howell’s group remained, and this was the common pattern. Of the 1,816 officers and men who had left Hong Kong, only 970 answered their names, leaving 843 (taking into account the three who escaped) who were assumed to have been killed or drowned. When the roll call was complete, the Japanese issued each man a light corduroy jacket and trousers, a shirt and a pair of felt slippers. This was to be their only clothing for the next few weeks in the cold Japanese weather, and these items turned out to be infested with lice.

Shanghai to Japan

35 of the prisoners who were seriously ill were left in Shanghai and the remainder were then loaded in the holds of a Japanese transport, the 'Shensei Maru', in conditions similar to those on the Lisbon Maru. Dysentery and diphtheria were now rife and the men in poor shape, five of them dying on the journey to Japan. The ship docked at Moji on 10 October, where 36 of the worst cases of dysentery were removed to hospital. The remaining prisoners were directed into two groups, the larger, consisting of about 500 men, destined for Kobe, and the remainder for Osaka. Press representatives spoke to some of the prisoners, who had been warned not to speak freely about their experiences because of inevitable reprisals, for it was obvious that the Japanese would not tolerate an accurate account of the matter. This reticence enabled the Japanese to claim that: 'with one voice and in the highest possible terms these surviving British prisoners referred to the strength and warm heartedness of the Imperial Forces, and lauded the gallantry of the Japanese.'

To their great surprise, the prisoners were loaded on a comfortable passenger train at Moji and were provided with regular meals of excellent quantity and quality. After several hours travelling, the train stopped at a station and an announcement was made that the prisoners who were most ill would be taken off the train and sent to hospital. About 50 of the worst cases were dropped off at Kokura, where 21 of them died, and others were off-loaded at a place which was later to become well known: Hiroshima. The remaining 326 were carried on to Osaka, where they were accommodated in barracks in the middle of the town.

The prisoners had now lost all their possessions for the second time. At the time of surrender in Hong Kong, those who had been out in the hills lost everything except that which was carried in their haversacks. In the ensuing months, they had managed to buy, scrounge or purchase through the wire some modest necessities. Now everything was lost once more and they had nothing except the clothes on their backs, not even a towel, soap, toothbrush or handkerchief, and it was many weeks before they obtained these necessary articles.

The Casualties

The men were so weakened by their experiences that casualties were high during the next few months. Lt. Col. Stewart and Capt. Cuthbertson both died soon after arrival. During the first year in Japan, 244 died: 114 in Kobe, 55 in Osaka, 21 in Kokura, 24 in Moji and an estimated 30 in other places. Most of them could have been saved by proper care and attention. Thus, out of the original 1,816 officers and men, 843 were drowned or killed during the sinking, 5 died on the Shensei Maru en route to Japan and 244 died subsequently in Japan, making a total of 1,092, leaving just 724 survivors. Of those who died, some (in particular members of the Royal Artillery in No. 3 hold) were drowned before they could leave the hold; some drowned in the sea; some were shot; some were killed on the rocky shores of the islands; some died of exposure and exhaustion, and some of disease.

In December 1942, the Japanese Army Secret Order No. 1504 contained the following: 'Recently, during the transportation of prisoners of war to Japan, many of them have been taken ill or have died, and quite a few of them have been incapacitated for further work due to their treatment on the journey, which at times was inadequate.' Instructions then followed: 'those prisoners should arrive at their destinations in a condition to perform work.' This order had little effect, and in March 1944 Vice Minister for War Tominaga, foreseeing the wrath to come, drew attention to the high death rate among prisoners, and added: 'If the present conditions continue to exist, it will be impossible for us to expect world opinion to be what we would wish it to be.' How right he was!

Further Reading

A number of books have been written about the incident. There is also quite a lot of information on the internet as well. Some of the links are in the text above. Also please try these sites for further reading:

Role of Honour – by Ron Taylor (Roll-of-honour.org.uk)

Web site dedicated to Chinese Fishermen – who rescued British PoWs from the Lisbon Maru

Far East Heroes web Site - related to FEPOW web site

Previous page: Shamshuipo Camp

Next page: Hiroshima PoW Camp