Shamshuipo Camp

Most people imagine that, at surrender, the garrison was taken prisoner en masse. In fact, prisoners were taken from the very start of the fighting and the Japanese had to find different places to intern them. In January 1942, they rationalised their camp system. North Point became the Canadian and Royal Navy Camp; Shamshuipo became the British Army and HKVDC Camp; Ma Tau Chong was opened as the British Indian Army Camp, and ‘enemy’ civilians were sent to Stanley Internment Camp, Rosary Hill and Ma Tau-wai.

Shamshuipo, where the British were held, is situated in the north western part of the Kowloon Peninsula in Hong Kong. Descriptions of this camp invariably focus on the different diseases suffered by POWs interned there, in particular epidemics of diphtheria and outbreaks of malaria.

This was the situation until early September 1942, when the first transportation of POWs to Japan took place. In total, nearly 2,500 men were removed by ship, primarily from Shamshuipo (in Cantonese Chinese this name means Deep Water Pier).

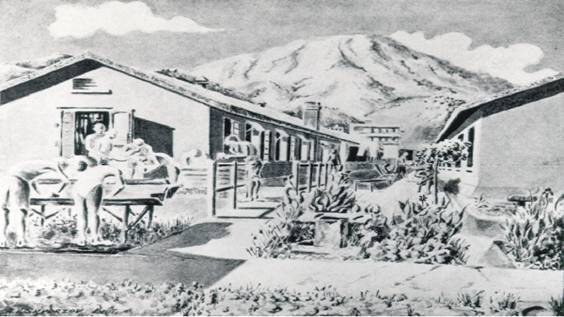

Above: Huts in Shamshuipo Camp, 1942-45. From A. V. Skvorzov, Chinese Ink and Brush Sketches of Prisoner of War Camp Life in Hong Kong, 25 December 1941-30, August 1945, A. V. Skvorzov, 1945.

Reactions among the prisoners of war were mixed. After the initial shock of the surrender on Christmas Day 1941 had been absorbed, hopes had run high for an early release, but it soon become apparent that no relief was to be expected from the Chinese Army. Singapore and the Philippines had fallen to the Japanese and the news from the European theatre was bad.

On 25 September 1942, 1816 British prisoners of war were assembled on the parade ground of Shamshuipo Camp, Hong Kong, and were addressed by Lieutenant Hideo Wada of the Imperial Japanese Army, through his interpreter Niimori Genichiro.

'You are going to be taken away from Hong Kong,' he said, 'to a beautiful country were you will be well looked after and well treated. I shall be in charge of the party. Take care of your health. Remember my face.' Read more in the Interview with Maynard Skinner.

Some prisoners argued that a move to Japan, which seemed the obvious destination, would be an improvement since (they believed) the Japanese would not wish to display in their own homeland their inhumanity to prisoners of war and that consequently better treatment might be expected. The more cynical scorned these ideas and would have preferred to stay in Hong Kong, where perhaps the chances of rescue and escape were slightly greater. But discussion was futile, for a prisoner of war has no choice of action.

Albert Ient - Third Draft: From Shamshuipo to the Japanese Mainland

This is how it was for my dad, Albert. Tony Banham, from the FEPOW Community, advised that he was on the Third Draft from Shamshuipo to the Japanese mainland; destination Habu, the principal township on Innoshima Island, and Hiroshima Prisoner of War Camp. In an email, dated 19 March 2007, Banham explained where he got this information from:

'The Japanese employed Chinese clerks in various functions. These clerks had no love for the Japanese, but it was that or starve. The Camp maintained lists of all POWs. One clerk decided, on his own initiative, to take a sheet of this list home each night, copy it with his own typewriter, then smuggle it back next morning. He did this until he had copied all 8,000 names, and then he put it in a briefcase, escaped to China, and handed it to British authorities there. The daughter of the man he gave it to kept a copy which she passed to me [Tony Banham]. By many names, such as A.V. Ient, there is a number indicating which draft they were on. In Ient’s case it is a 3.'

For further reading on this topic see - Transcript of The Prisoner of War Diary of Staff Sergeant James O’Toole.

See the website: Prisoners of War in Hong Kong and Japan, 1941-1945 by Charles G. Roland for more photographs of Shamshuipo.

See Memories of a Volunteer by Arthur Gomez’s for very moving memories of his time in this camp 1942-45.

Previous page: Commander's War Diary

Next page: The Sinking of the Lisbon Maru