Albert Ient

Albert Victor Ient, my father, was born on 5 December 1905, the youngest child of Charles (formerly Karl Gottlob) Jent and his second wife Julia Ann Thurley Hemmings. Dad's birth certificate originally recorded his name as Albert Herbert Jent, but this was corrected to Albert Victor Ient. Albert was named after the Victoria and Albert Museum by his father, Karl, who at the time was a senior stone mason on the museum's construction. The family lived at 5 Warsill Street, Battersea, London.

|

|

A picture of Albert Ient taken in Hong Kong in about 1940. |

|

|

Albert Ient was a soldier in the Royal Signals and afterwards a key figure in the Royal Signals Association. This is a copy of a plaque presented to him when he was president of the Aldershot Royal Signals Association |

I talked to Dad about his life, but clearly not enough, so I only have a sketchy history of his life before I was able to remember him (from the age of about 4) in 1949/50. By that time, he was already nearly 50 years old and had gone from growing up in London to various postings with the army, including camps in England and postings in Malta, Egypt and Hong Kong. He finally came home in 1945 after three and a half years in a PoW camp in Japan.

In this biography, follow these links to go to the section you are interested in:

London

The Army – in England

Malta

Egypt

Hong Kong

Christmas Day 1941 – the Fall of Hong Kong and Prison Camp

Japanese Prison Camp

The End of the War and Return Home

Aldershot – 1946 onwards

Medals

Epitaph

London

Dad grew up in Battersea. For more on the family, see Karl Ient's biography. We only have two photos of Dad as a young boy:

|

|

Albert Ient when he was about 4 in 1910. |

|

|

An earlier picture is of with him sitting on his father Karl's knee, dating from around 1908 or 1909, when he was about 3. |

|

|

Albert when he was about 12 (1917). |

He was a choirboy at Southwark Cathedral, which must have been between the ages of around 8 or 9 to 14 or 15. Certainly, I remember him telling me that his voice broke and he could no longer sing. His ultimate accolade was to be chosen as lead choirboy in the Southwark Cathedral Choir. He was clearly of some significance in terms of the choir, because there are apparently recordings on cylindrical disks of him singing at Westminster Abbey. He was very proud of this; he sang standing on the grave of Lady Jane Gray in the Chapel of St Peter un Bincula at Westminster Abbey. He sang Basel Dean's production of 'God's Goodman Chorister'. The organist was Stern Dile.

Dad recalled going to Southwark Cathedral twice on Sundays, journeying first to attend the morning mass, returning home, presumably for lunch, then going back again for evensong in the evening. It is quite a distance from Battersea to Southwark Cathedral. I think I remember him saying he walked most often. Dad could read Latin and I assume he learned this because it was taught at Southwark Cathedral. He also sang at St Saviour's in Battersea.

The Army – in England

|

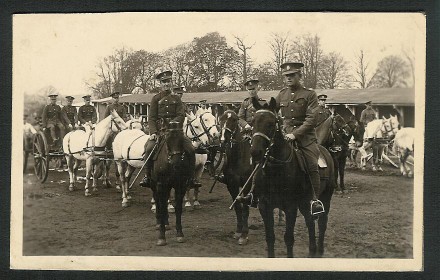

Following his brothers' lead, Dad enlisted with the 13th London Regiment (TA) on 13 September 1921. Army No. 6653403. This was known as the Kensington Regiment. Two years later, on 28 December 1923, he transferred to the Regulars and the Royal Corp of Signals. The next six years were spent at Signal Training Centres in Maresfield or Aldershot, and most of that as a mounted linesman with 'D' Troop Cavalry Division Signals. In those days, being a linesman meant providing the telecommunications for the army; a linesman was usually required to erect and construct telegraph lines, which would connect the headquarters through to the main divisional army unit in the battlefield. |

In the post-WWII years, Dad was very keen to keep up with army contacts. This is a copy of the front cover of a Regimental magazine of his original Regiment – The Kensington Regiment. |

At Maresfield, Dad had his first experience of being a horseman.

He loved horses from then on. Unfortunately, I only have the briefest insight into his life at this time. When I first moved to Sussex, he joined me in the car and as we came down through into Lewes we passed The Volunteer pub and he said to me that it was the first pub he went to as a young soldier, during an evening pass from the camp at Maresfield. In those days, you could get a train from Maresfield, directly through the countryside to Lewes, getting off at the station behind the old library, just off Cliffe High Street.

He loved horses from then on. Unfortunately, I only have the briefest insight into his life at this time. When I first moved to Sussex, he joined me in the car and as we came down through into Lewes we passed The Volunteer pub and he said to me that it was the first pub he went to as a young soldier, during an evening pass from the camp at Maresfield. In those days, you could get a train from Maresfield, directly through the countryside to Lewes, getting off at the station behind the old library, just off Cliffe High Street.

As you can see, the Signal troops, who laid cable on the battlefield and behind the lines, where still mounted in the 1920s:

Albert Ient in the centre at the front as a young soldier about 1922. This photo was probably taken at Maresfield.

Other military photo in England pre WWII:

|

|

This picture is named & dated on the back as: Tidworth 1929. This is from Albert's collection though we don't know which soldier is him. |

|

|

Dad was a crack shot with a rifle, and this picture form the 1930s shows him with the winning team in an army competition at Bisley camp in Surrey. John Ient has the shield which Dad was awarded. Albert Ient is in the front row on the far right. |

Malta

On 13 November 1929, Dad was posted abroad to Malta where he met his wife, Myfanwy Edwards from Abertridwr, Caerphilly. One of Dad's jobs was to collect signals (like telegrams) from the Signals HQ and take them to one of the officers' home in Malta. My mother, at the age of 18 years, was a servant working at this officer's house, which also served as a military office. She had noticed him coming and going and eventually, because my father had said nothing, she spoke to him and that started their relationship. They were married on 10 September 1932 at the Cathedral Church of St Paul in Valletta, Malta.

Malta was where my eldest brother, Tommy, was born, on 1 April 1933, and my second eldest brother, John, was born on 2 September 1934. The family returned to England on 29 January 1935, in time for the 1935 Jubilee celebrations, and made their home in Army Quarters (a rented house) at Frimley Green. For more history and photos of their time in Malta, see the article on Albert and Toby's Life Abroad.

Egypt

But Dad was not still for long and on 14 September 1935 he disembarked in Alexandria, Egypt, for service with 'Bare Defences Mediterranean' (this is how my father described the military mission - further research is needed). It may have been to do with the 1936–1939 Arab revolt in Palestine. His work involved putting up telegraph and telephone lines in the desert. He was away from his family until 7 August 1936. Pictures from Egypt:

|

In Egypt. |

This picture is dated: Christmas Day 1936. Albert Ient is in the centre. |

Two years later, after the birth of his third son, George, on 24 July 1937, Dad was posted to Ceylon. However, in discussions with his friends, he changed his posting to Hong Kong, a near fatal decision as far as my Dad was concerned, considering his wartime situation. Dad left on 14 December 1938, and Mum and the boys followed some time later.

Hong Kong

1939 was the peak of Dad's military career. Mum joined him with the 3 boys in 1939. Though the war was on in Europe, the Far East was at peace, albeit uneasy. Japan did not strike for nearly another 2 years (December 1941).

Albert Ient – second from the left in the front row.

This went well until 21 February 1940, when sadly, very sadly, my brother Tommy (the eldest) died falling from the roof of the residential block whilst playing with other boys. This event set the scene for 1940, because later that year, in the summer around July, Mum had to be evacuated with John and George, first to the Philippines (Baguio, Manila) and then to New South Wales, Australia. At the time of their departure, Dad had a broken leg, following an incident at work on 25 May 1940, and he was in hospital. For more history and photos of their time in Hong Kong, see the article on Albert and Toby's Life Abroad.

Christmas Day 1941 - The Fall of Hong Kong and Prison Camp

Dad fought in the battle for Hong Kong (see Wikipedia). The Japanese attacked on 8 December 1941. I asked Dad about the battle and capture. He said that he led a small group of soldiers who were on guard at The Peak on Hong Kong Island. On Christmas Day 1941, they were told to lay down their arms. He remembered surrendering to a group of Japanese soldiers who were led by a young lieutenant (Dad said 'He was like a boy of 15.'). He said this was the most terrifying event of the battle, with the young lieutenant's gun shaking in his hand. I believe the location was Mount Austen Road, The Peak. Following capture, like all the soldiers in Hong Kong, he was confined in Victoria Barracks for one week after the surrender.

|

Japanese soldiers in Queens Road, Hong Kong. |

Above: Huts in Shamshuipo Camp. 1942-45. From A. V. Skvorzov, Chinese Ink and Brush Sketches of Prisoner of War Camp Life in Hong Kong, 25 December 1941-30 August 1945, A. V. Skvorzov, 1945. |

They were then force-marched to a place called Shamshuipo, in Kowloon in the 'New Territories' on the mainland, probably via the Wanchai ferry, for internment as a prisoners of war.[2] From there he was amongst the third draft of Allied soldiers to be transferred to Japan.[3]

Japanese Prison Camp

Dad was shipped to Japan onboard the Tatsuta Maru, an ex-cruise liner, for the three day journey which included crossing the Inland Sea to Innoshima.[4]

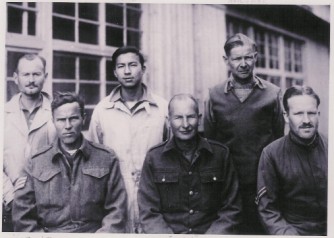

On the 23 January 1943, he disembarked in the village of Mitsunosho and, along with 99 other HKDVC prisoners, marched half a mile to Habu, the principal township on Innoshima Island, to Hiroshima Camp #5, the camp where he was held for the rest of the war.

Prisoners were photographed in groups of six on arrival. This photo is taken at the Habu camp on the Island of Innoshima (Hiroshima Camp #5). Albert Ient is on the far left in the front row.

I talked to Dad about his experiences in the PoW camp, but sadly I didn't make notes at the time. However, I have been lucky enough to meet two ex-servicemen who were PoW in Japan – one with him at Innoshima (Hiroshima Camp #5) and the other who served with him in Hong Kong and was a PoW at another camp. For their stories, see the links to Terence Kelly and Maynard Skinner.

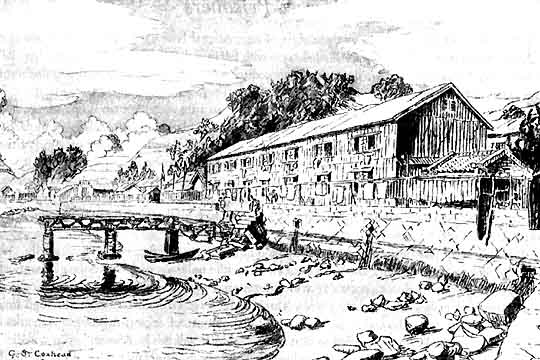

Terence Kelly gives a very detailed description of life in the prison camp in his book Living with the Japanese (recently re-published under a new title, Hellship to Hiroshima). Another fellow prisoner of Dad's, Geoffrey Coxhead, drew detailed pictures of the camp and the inland sea around Innoshima. Dad was sent a copy of this one after the war by Geoffrey:

This picture shows the camp hut in Habu camp where Albert Ient lived for three and a half years, with the damaged bridge in front. This bridge was bombed by the US Air Force in 1945.

I do remember Dad telling me of his experiences during the time as a PoW:

Prisoners worked on the building of ships alongside Japanese workers. Dad told me of the cold winters; if you touched the metal of the ship, your hand could be frozen to the metal and strip your skin. Work was monotonously routine – starting with reveille at 5.15 am & finishing at 7 pm (towards the end of the war).

On one occasion, he recounted to me that they were all marched into the sea and told to stand to attention in the rising tide. This was all over a missing bag of rice. It probably wasn't one of the prisoners but someone had to own up.

The biggest problem Dad faced during the war and immediately after was suffering from beriberi. This is a condition caused by the lack of vitamin B1. Its symptoms include, amongst others, weight loss and the bloating of the body. This bloating could happen very quickly – in a matter of an hour. After the war, Dad suffered from boils. I remember these being quite ugly things. I think they went on until about 1952. All of this was because of the lack of proper food. An example is that Dad said they often had to eat cooked soya bean husks rather than the bean itself.

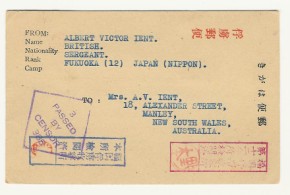

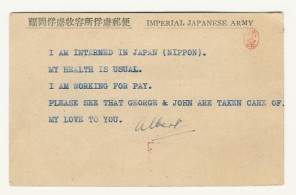

Like the other prisoners, they received no Red Cross parcels or letters until later on in 1944 (over 2 years). Dad wrote regularly to Mum on pre-typed cards, but these were not received by Mum until towards the end of 1945. Then she received them all!

|

|

|

Things were improvised in the camp. Here are two items – one made and used by Dad and the other probably came from bargaining with a prison guard, I am not sure:

|

Razor |

Glasses and home-made case |

Dad recalled that towards the end of the war the Americans started bombing and many of the bombs landed in the PoW camp (see the picture above). Hiroshima was only 25 miles away over the hills, but like other PoWs and the Japanese at the camp, no one know about it even though it was so close. There had been so much bombing. He also recalled the first American troops; he said they were all black. It is true that the US army did have all black regiments.

The End of the War & Return Home

The Japanese surrendered unconditionally on 14 August 1945 and on his release Dad was taken by boat to Onomichi (an industrial town between Hiroshima and Okayama), then by train to Osaka and finally HMS Ruler, a British aircraft carrier, took him directly to Sydney, Australia.[5] The photo below is of HMS Ruler:

Unfortunately, when he arrived in Sydney on 27 September 1945 he found that his family had already left.

On 17 October 1945, Dad went on board the Dominion Monarch (coincidentally, the same boat Mum and my brothers had sailed back to England on). The original embarkation date had been set for 15 October, but this was delayed; he eventually set sail for home on 18 October 1945. The journey took him via Fremantle and Suez (Aden – 3 November, Port Said – 7 November), eventually arriving in Southampton on (approx.) 15 November 1945.[6]

On 17 October 1945, Dad went on board the Dominion Monarch (coincidentally, the same boat Mum and my brothers had sailed back to England on). The original embarkation date had been set for 15 October, but this was delayed; he eventually set sail for home on 18 October 1945. The journey took him via Fremantle and Suez (Aden – 3 November, Port Said – 7 November), eventually arriving in Southampton on (approx.) 15 November 1945.[6]

Aldershot – 1946 onward

Dad was given family quarters at 9 Nicholson Terrace, Aldershot. I was born there on 9 September 1946. In this period, I understand Dad had a horse in the army. I guess this was good for him – he loved horses. For some reason, Dad decided to leave the army – I imagine he was sick of it. He joined the Post Office as a linesman. Basically, he started at the bottom of the ladder again. This new career with the Post Office Engineers was to last 23 years. He worked his way up to foreman and then area inspector in the Guildford Telephone Area.

He was a Life Member of the Royal Signals Association and he devoted much of his time and considerable energy to the Old Comrades Association. For many years, he was secretary of the very active Aldershot Branch, and in 1981 took on the role of president. His enthusiasm and interest in Corps matters was well known. In Dad's eyes, the bond of comradeship figured prominently; he was a soldier all his life in and out of uniform.

Medals

Sergeant Albert Victor Ient was awarded the LS, GC & Military Medal on 14 November 1946:

Left to right: the 1939-1945 Star, the Pacific Star, the Defence Medal, the 1939-1945 War Medal, the Meritorious Services Medal, the Good Conduct and Long Service Medal.

Epitaph

Albert died on 9 February 1988 in Farnham Hospital, Surrey. The cause of death was Broncho Pneumo, Carcinomatosis and Carcinoma of Prostate.

He is greatly missed.

It was his wish to be cremated and his ashes are buried at Aldershot Crematorium along with my mother's.

This was his epitaph in the Royal Signals Journal:

[Please note: he was known as Vic to his army colleagues and indeed to everyone except Mum and the family.]

[1] Maidservant or nurse. Originally from Portuguese.

[2] War Diary of Chief Signal Officer, p1 Foreword by Lt Col Truscott.

[3] AVI member of Third Draft confirmed by Tony Banham FEPOW Community - see attached notes on his source of information.

[4] Innoshima is in the Ken (English equivalent is county) of Hiroshima.

[5] See T Kelly interview notes.

[6] Source letters from Albert to Toby 17 and 20 October 1945.

Previous page: Thomas Ient

Next page: George Ient